As any scribe will tell you, a medieval manuscript consists of calligraphy, and illuminations – the flourished capital letters, borders and other illustrations that augment the text. So to set the tone for what’s coming next, I will share a snapshot of medieval life in Carcassonne, as told through a piece of street art that I spotted a short distance from the walled city. The entire work runs the length of a city block.

Each panel connecting the illuminated letters depicts a point in history or an aspect of royal life in Carcassonne, as noted in the white shield at the lower right of each panel. This panel tells the story of the Franks, led by Pepin d’Heristal, called ‘the Short,’ in an alliance with the Visigoths who had held the city since 410 AD before the Arab invasion of 725, chasing the Saracens out of the city in 759.

The knight in the letter bears the heraldic arms of House Trencavel, a French noble family who ruled the viscounty between the 10th-13th centuries and who built a castle within the walls of the city in about 1130. The connecting panel shows a boar hunt with dogs and spears.

The hunt is a success, the boar is felled, and a banquet ensues.

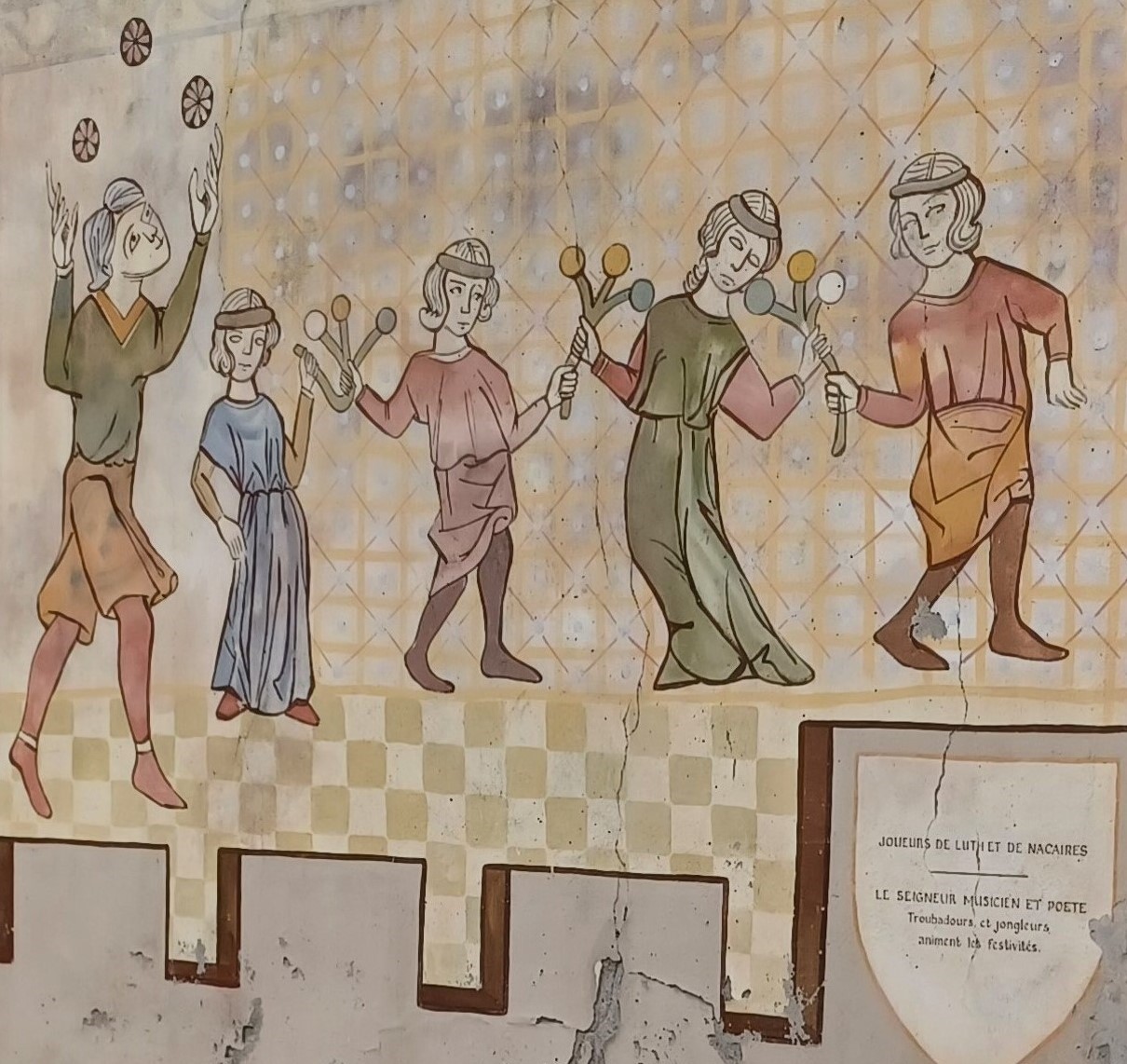

Lute and horn players, troubadours and jugglers

The Court of Love. The courtyard of the Trencavel Castle would have been shaded by plane trees (plantanes), with an elm tree at the center – the secular symbol of nobility in this region. Under that elm tree, the troubadours meet to compete in literary jousts, and the chevaliers combat under the colors of his lady.

After the Fallen Angel, the next panel shows a woman spinning, two men (perhaps carrying the wool to market), grapes being crushed for wine, and a ‘depiction of the Cathar Religion.”

The Cathars were a Christian sect that appeared in France in about 1165, during a time of Gregorian reforms which separated “Church from State” and allowed churches to retain revenues they had previously paid to the royalty, which had the effect of the churches losing the support and protection of the nobles. Cathars held dualistic views – a good deity symbolizing heaven, and an evil one symbolizing the material world. The were heavily persecuted during the medieval era for their heretical views.

An angel not fallen. The next panels shows Saint Dominic trying to convert the Cathars to the Dominican Order in 1206. The Cathedral of St. Nazaire (which will I detail in an upcoming blog) had been consecrated in 1150. While the Cathar religion spreads through the Toulouse region, Pope Innocent III calls for a remedy, which inspires the Albigensian Crusade in 1209. Over the next twenty years it would crush the Cathar movement, and leads to the establishment of both the Dominican Order and the Inquisition in France. It also throws Carcassonne in the direct path of the Crusaders, who had come to root out the Cathars, many of whom had taken refuge within the city walls and were therefore under the protection of Viscount Trencavel.

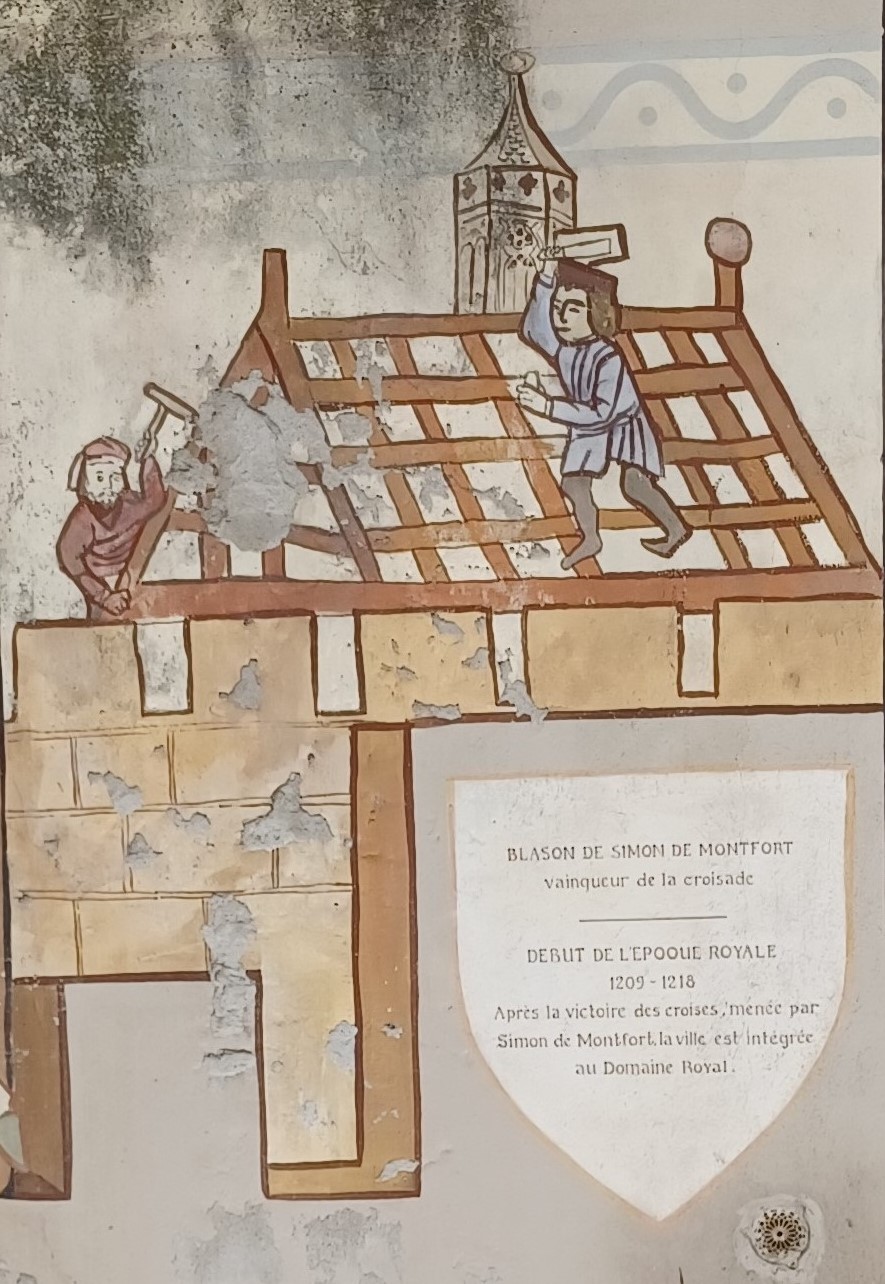

Viscount Raymond Trencavel defends Carcassonne against the Simon de Montfort and his French knights in 1209. The siege lasts for two months, after which Simon de Montfort is declared the winner and takes over the city. The informational shield says “representation according to the Siege Stone.” This stone is reportedly inside the Cathedral, although I did not know to look for it when I was there.

This knight bears the arms of Simon de Montfort. The connecting panel shows the Siege of Carcassonne. Simon de Montfort will also take Toulouse in 1216 but will be killed two years later during a siege on that city, led by Raymond VII of House Trencavel. Raymond would also lay siege to Carcassonne in 1223 to regain control of the city from the Montforts, which he wins the following year.

Louis IX, King of France and leader of the Crusade, enters Carcassonne in 1226 without a show of force. (Louis IX remains the only French king ever canonized. The other half of Carcassone – Bastide St. Louis – was built during his reign and is named after him.)

The connecting panel shows “From Saint Louis to Philip the Bold (Louis’ son), construction of the second enclosure of the city from 1226-85, and the foundation of the lower town in 1247.” The Cathedral is completed in 1332. The lower city, which served as the administrative center to Carcassonne, is destroyed by Edward the Black Prince in 1353.

The final E is occupied by an unnamed French queen. The artists’ credit and contact information ends the series.

Carcassonne has a history much longer than that depicted on this wall. From the 1st century BC it was a Roman settlement known as Carcasso. Development of its fortifications started during the 4th century. You can still see remnants of the Roman walls – look for the red bricks, which Roman masons used as levelers between the stones.

The city was renamed Carcassonne by the 15th century and remained mostly isolated from the religious wars of the next two centuries. The French Revolution proved destructive, with many buildings burned and the city dwellers tearing stone from the battlements to build (or perhaps rebuild) their own homes.

Just as the city was about to be sold to a stone quarry in the 19th century, two men – Jean-Pierre Cros-Mayrevieille and Prosper Mérimée – stepped in and influenced members of Parliament and Prince Bonaparte to fund restoration. Work began on the cathedral in 1844 and the rest of the walled city from 1852-1910, and focused on restoring the battlements and roofs to many of the towers. The restoration was strongly criticized during Viollet-le-Duc’s lifetime. After having finished a project in northern France, he made the error of using slate instead of terracotta tiles. Slate was not a local stone to Carcassonne, but was a more typical roofing material in the north, as was the addition of the pointed tips on the roofs.

Regardless, we have these men to thank for restoring the walled city and conserving its history within its walls and towers.

Illuminated, Medieval graffiti! Incredible and informative!

LikeLike

I know! It is brilliant!

LikeLike