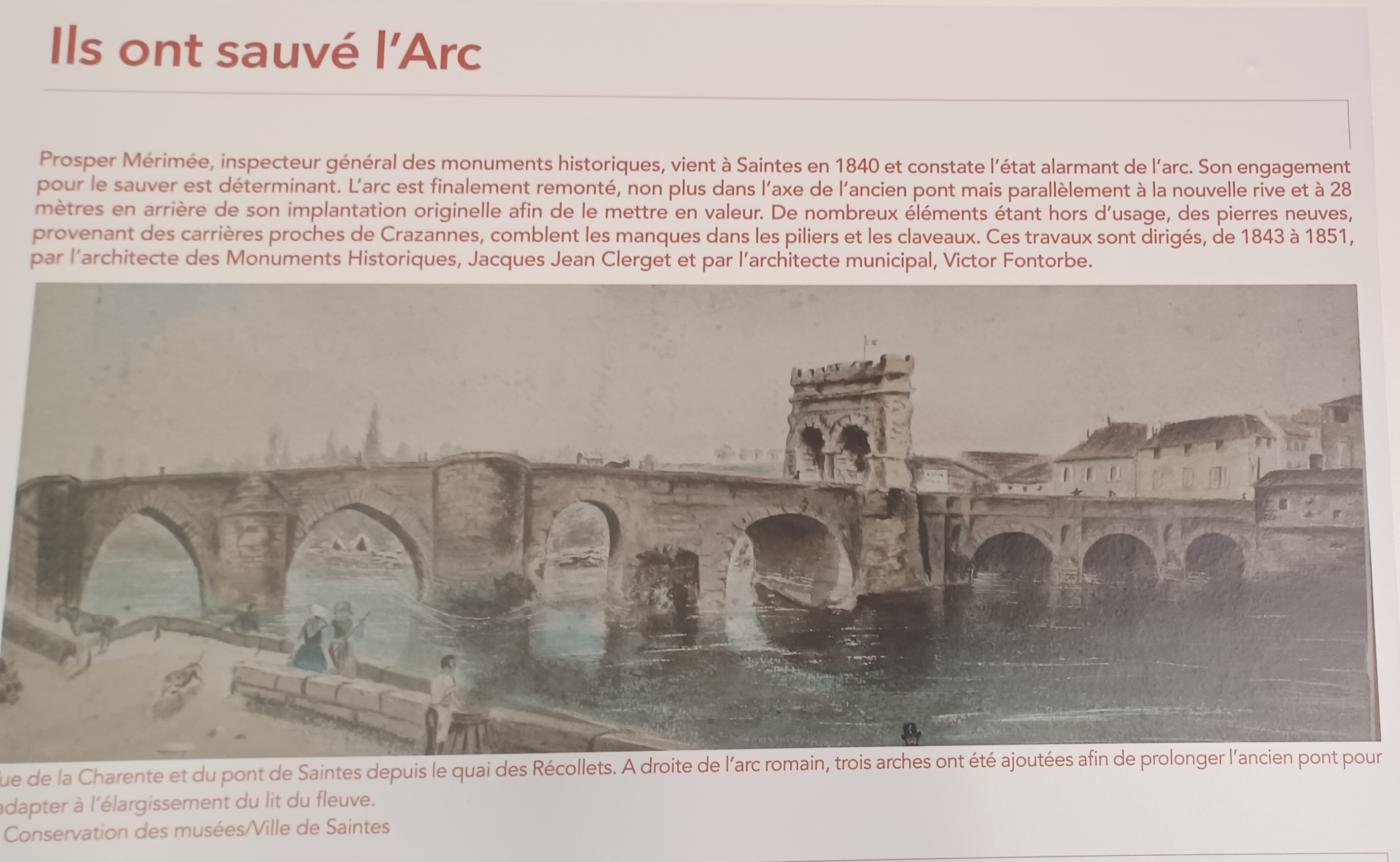

Before Saintes was French, it was Roman. And because it has clung to its heritage, it has a very different vibe from the other cities I’ve been to this trip. The famous Green Line takes me from the abbey straight to the town square and the Arch of Germanicus, erected in 18-19 AD and dedicated to Emperor Tiberius. It was the gate that marked the end of Via Agrippa, the Roman Way from Lyon and entrance to the city over a stone bridge that had been destroyed in the 18th century In the mid-19th century the arch was moved 28 meters behind its original location, reassembled and repaired.

It is especially dramatic at night when the lights turn it red.

To the left is the tourist office, and the archaeology museum which I will visit later. A large enclosed building is next to that. I stick my camera through the latticework. I think it might be a stable, but find out later it was an abattoir (slaughterhouse). According to my guidebook it was built in the 19th century on the site of an earthenware factory that stood here 100 years earlier. The columns in front are remnants of monuments that were destroyed at the end of the 19th century, placed here to dress up the space.

Saintes was named after the Gallic tribe that had settled here in the 3rd century BC. It became a Roman territory at turn of the 1st century. Under Augustus Caesar, a town was built at the end of the Via Agrippa and named Mediolanum Santonum, “the central town of the plain.” It served as the capital of Roman Aquitania until power shifted to Bordeaux sometime in the 2nd century. The wall that once surrounded this roman city was destroyed during the French Revolution.

I follow the Green Line up a steep but picturesque hill, turning back every so often to catch my breath as well as some shots, because the Green Line reminds me to : ) In Nantes I learned that the black metal posts in the second photo are parking permit readers, which lower the metal posts that block the street to vehicular traffic. I saw a similar system in Istanbul. I also figured out that the metal bumps embedded in sidewalks and walkways in France, indicate curbs and staircases for blind people. I thought that was pretty clever.

I stop at the bibliotheque, what the French call a library (conversely, a library here is actually a bookstore). I walk over a delightful mosaic floor and into a courtyard that surrounds the bibliotheque. I stop to admire its windows edged in wonderful Art Nouveau stained glass. There’s also a doorway with a beautiful glass and iron canopy.

I’m walking, and walking, the Green Line leads me through a parking lot edged in graffiti, and a Saturday market that is small but very fragrant, with vendors selling flowers, baked goods, fruits and seafood. And I’m walking and walking …

I pass the Saint Louis church, not open today. Built between 1600-10, it was the administrative building for the Saint Louis hospital and later became the governor’s residence. Across from this building is a city park. I have become very appreciative of the public spaces here. I find wooden lounge chairs, and a picnic area, gardens, and installation art pieces designed to look like telescopes but are just iron pipes, pointing to about a dozen landmarks across the city.

The Green Line continues to guide my path until it abruptly stops mid-step. No worries – there’s only one way to go from here. I stroll a path, past a long stone wall, and see these stone cairns but can’t figure out what they are. Graves? Capped wells? Why are they fenced in? (I would find the answer at the Archaeology Museum the next day.)

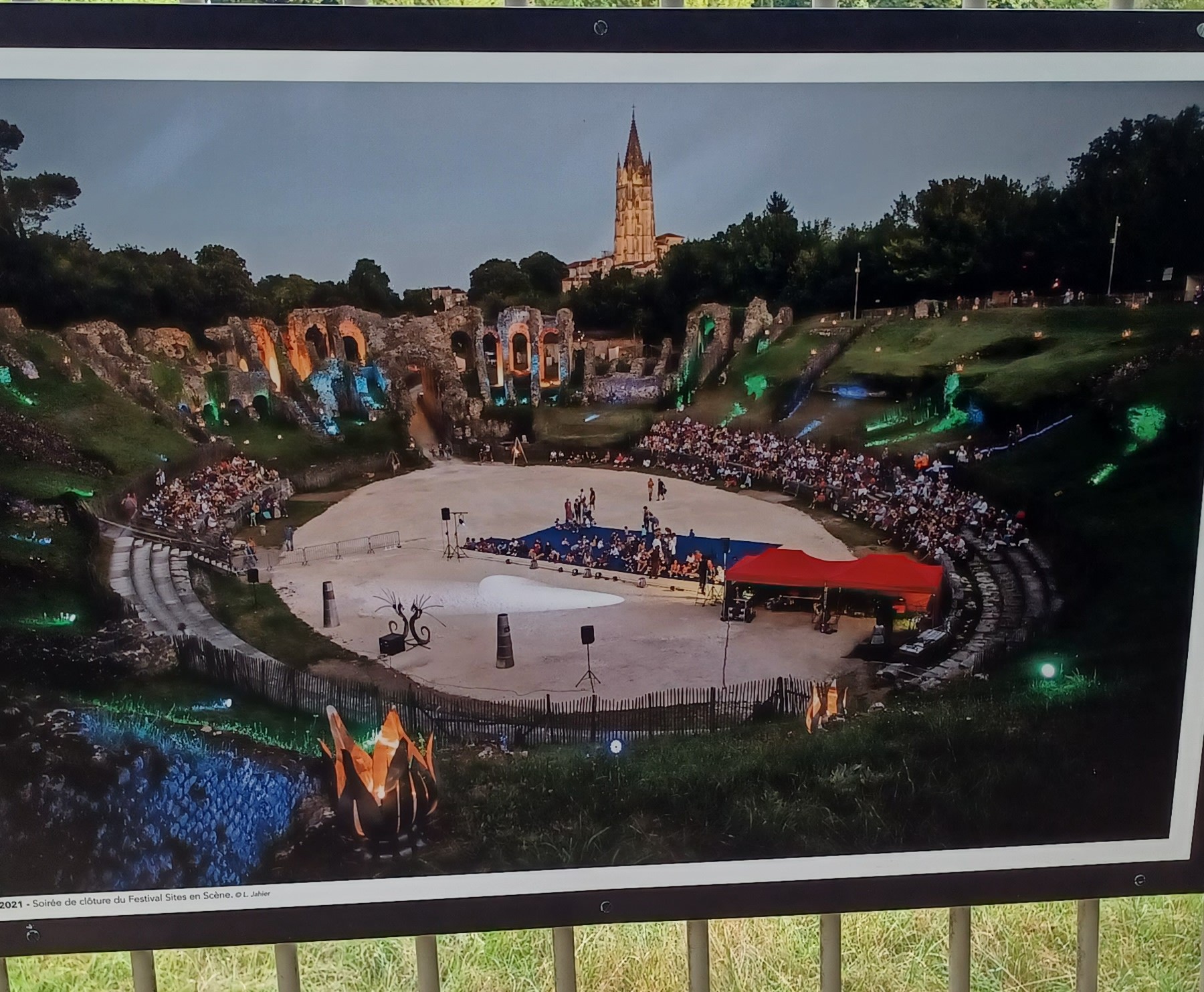

About an hour after I have left the abbey, I arrive at the amphitheater. It was built during the reign of Claudius in 40 AD, and is one of the oldest in Gaul (Belgium-France).

No trip to Europe is complete without finding at least one site in each city that is sheathed in scaffolding with restoration efforts underway. There is also drainage pipe being laid in the floor of the arena, which floods regularly.

The amphitheater was built in a vale – a natural bowl – which allowed builders to set seating for up to 15,000 people into the natural landscape rather than having to build a surrounding wall.

There were gladiator fights and animal hunts here. If you opt for the English audio guide, it will walk you down to the floor of the arena, where you get a better view of the seating, as well as glimpses of the two entrances – the Sanavivaria Gate (Gate of the Living) where victorious gladiators emerged, and the Libitinensis (Gate of the Dead) where dead gladiators and animals were carried out, to be buried in a nearby necropolis. There is also a fountain here, dedicated to Saint Eustelle, although I could not spot it.

There are posters along the fence showing its more modern uses. It was used as a stone quarry during the Middle Ages, and the first documented equestrian event was held here in 1560. It was declared a historic monument in 1840, with restoration work beginning in 1870. In more recent centuries it hosted festivals and operas.

I remember to eat twice today – a salad for lunch which came with bread and dipping oil – a condiment I have not seen served with bread outside of Italy. Dinner was a three-course meal aboard a floating restaurant, which in spite of an English menu and an English-speaking waitstaff, was full of surprises. I end my day with a walk along the waterfront.

And on that note, Gracie says “good night.”

Wow, that Roman amphitheater, built in a vale, is impressively old and fittingly grim, in a way. Fascinating stuff; seeing the Roman influences in that corner of Gaul!

LikeLike

It is grim, knowing the violence of the games that were played here. I did not expect to walk on the floor of the arena, but I chanced the wooden stairs to do so.

LikeLike